![]()

By LAMBETH HOCHWALD

In 2007, when actress Marcia Gay Harden’s mother, Beverly, began showing signs of forgetfulness, Harden wasn’t sure what to make of it. The first incident occurred when the two attended a charity event in Canada and Beverly kept losing her passport, finding it and losing it again.

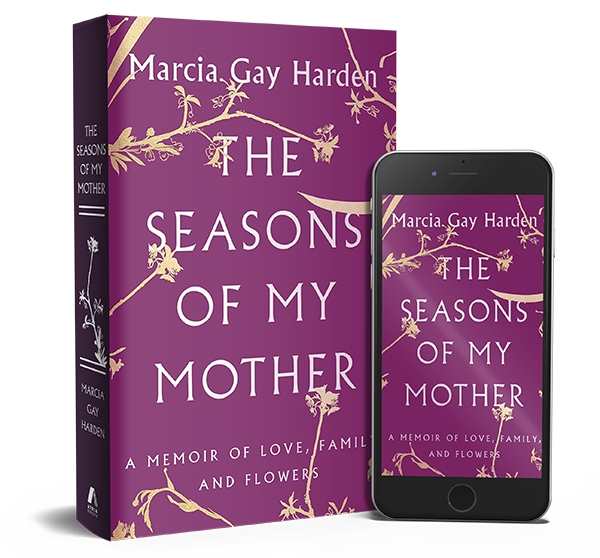

At a press junket and premiere months later, she acknowledged that she wasn’t sure what day it was. As time passed, those forgetful moments became regular occurrences and, in 2011, Beverly was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. This week, the Academy- and Tony award-winning actress’ memoir, The Seasons of my Mother: A Memoir of Love, Family and Flowers, publishes and, with it, comes a touching story of a mother and daughter, filled with childhood stories and memories. Parade sat down with Harden, a mother of three who is currently appearing on CBS’ Code Black, to learn more about the evolution of the book and how she hopes to help every family affected by Alzheimer’s.

It seemed to be a big turning point for your family when your mom kept losing her passport.

It was a penny drop moment. I didn’t quite understand it at the time. It was the beginning of the signs which became much more apparent and you couldn’t be in denial about them anymore. The prick of warning was more than a prick. It was a sharp pain. It certainly was for her as well. Her fear of what was ahead was scary for all of us.

How long did it take to write the book?

When I began writing the memoir, it was four years ago. Then I stopped for a year and a half. It was painful and I think I didn’t want to finish it because I didn’t want to say goodbye. My mom is still here—she’s now 81—but there’s a part of me that didn’t want to finish the book. Last Mother’s Day I said ‘Come on MGH—get it done.’

The book is punctuated by stories of your mom’s expertise in ikebana, the art of Japanese flower arranging.

My mom and I were going to write a calendar book about flowers and, as her memory began to dissipate, I wanted her to be remembered for it. Ikebana defined her, she learned it when my father was stationed in Japan in the midst of the Vietnam War, and it was a pathway for her artistry to release. The flowers became a metaphor I wove through the book. As the book unfolded it became clear that each chapter would be connected to either a flower in season or a memory surrounding flowers.

You write about your own concerns about being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s someday. How much do you worry about the disease?

Everyday. You can’t not. The beginnings of it are so mistakable with signs of old age—you walk into the room and you forget what you came in for, you forget where you put your keys and then find them in your back pocket. Nobody wants Alzheimer’s. It’s not a disease to make lemonade from lemons. There’s nothing good about it. I think about it every day and I try to do the things the latest research says to do, to cut the potential of getting it myself knowing it’s a thief that has the key to every lock on the block. It doesn’t care what block it’s on.

The book covers generation gaps—your mom wearing slips and you wearing Spanx—as well as conflicts over the years.

That’s intentional. If you’re writing a memoir it has to be authentic. You’re going to have to relate to all parts of the story, not just the glossy parts. Therefore you have to be irritated and grumpy and sharp with your mother. People will relate to that more than if you’re a Pollyanna about it. It wasn’t always easy to write but I do think that being personal makes it something readers will relate to.

What would you tell caregivers about taking care of themselves, too.

Everyone says make sure you take care of yourself and rest and I think that’s true but I think we instinctively want to take the disease away and make it better. Caregivers feel guilty that they can’t do enough, but you have to go easy on yourself. Being in the moment with the person, knowing they have an ability to recognize the familiar even if they can’t verbalize it, your familiar love validates them. They don’t have their memory to validate their existence. Memory is like a companion and they don’t have that anymore so just holding their hand is so important.

Can you share how you came to your verbal reaffirmation: ‘It’s OK if you don’t remember me, I will always remember you.’

There’s a phrase that says ‘even though they don’t remember you, you want them to know that they will be known, they will not be left adrift.’ What inspired me to write the book is that I will always remember her, I will remember for her. In the end, I want my mother’s legacy to be all the gifts she shared as a mother. That’s what I’d want my kids to give to me.