Zelda Fichandler, a seminal figure in the regional theater movement who led Arena Stage in Washington for 41 years, producing more than 400 shows and directing more than 50 for a company that helped spur the growth of professional theater around the country and became its centerpiece in the nation’s capital, died on Friday at her home in Washington. She was 91.

Her son Mark said the cause was congestive heart failure.

Ms. Fichandler (pronounced fitch-AND-ler), who had studied Russian at Cornell, was finishing her master’s degree in theater at George Washington University — her thesis was about Shakespeare in the Soviet Union — when she and her husband, Thomas Fichandler, along with a theater teacher, Edward Mangum, founded Arena in 1950.

The impetus to start a company in the first place, she later said, was that there was little theater to be seen in Washington — or anywhere else but New York — aside from amateur productions, summer stock, festivals and touring Broadway shows.

Indeed, the existence of a professional resident theater in the United States outside of New York was, at the time, nearly anomalous. They converted a former burlesque house and movie theater in a rundown section of the city to a 247-seat theater in the round and put on an ambitious first season of 18 productions, including three Shakespeare plays and works by Molière, Shaw, Synge, Gogol, Tennessee Williams and Oscar Wilde.

Mr. Mangum did not stay at Arena; he had a career directing overseas and elsewhere in the United States. Mr. Fichandler handled the business end of the theater. Ms. Fichandler, whose title was artistic director or producing director, was Arena’s artistic force until she stepped down in 1991. And though she never became a household name, she was a titan in the theater world, a visionary producer and teacher who was instrumental in seeding the American continent with the work of playwrights, directors, actors and designers.

Under her leadership, Arena became one of the nation’s leading theater companies and in the forefront of a regional theater movement that brought quality professional productions to communities from coast to coast.

Arena’s mission statement declares its dedication to American theater artists, but through its history it has ranged widely, presenting the plays of both American and European masters — Chekhov and O’Neill among them — and dramas by contemporary writers, including Arthur Miller, Tom Stoppard, Athol Fugard and Edward Albee.

Its numerous new works by emerging writers have included the American premieres of “Indians,” Arthur Kopit’s scabrous sendup of the mythology of the American West, and “Moonchildren,” Michael Weller’s portrayal of college students living communally; both ended up on Broadway. So did its production of the musical revue “Tintypes.”

In 1968, Arena became the first regional theater to send a play to Broadway when a trimmed-down version of its production of “The Great White Hope,” Howard Sackler’s extravagant stage biography of the boxer Jack Johnson that starred James Earl Jones and Jane Alexander leading a cast of 60 actors, opened at the Alvin Theater (since renamed for Neil Simon) and won the Tony Award for best play and the Pulitzer Prize for drama.

Arena was the first theater in Washington to play for integrated audiences, and in the 1960s it was among the first American theaters to employ a company of minority actors. In 1973, it was the first American theater sponsored by the State Department to tour the Soviet Union, where Ms. Fichandler’s production of “Inherit the Wind” appeared in Moscow and St. Petersburg (then known as Leningrad).

In 1976, it was the first theater to win the now-annual Tony Award for outstanding regional theater. Renowned directors who worked there included Alan Schneider, whom Ms. Fichandler said was among her main influences, Garland Wright, Elizabeth Swados and the Romanian Liviu Ciulei.

It was Ms. Fichandler’s belief, however, that the actor is the central element of the theater — “because it’s the behavior of the actor, the experience of the actor that reveals to the audience who they are,” she said — and that an acting company best allows the actor to thrive.

It is no surprise, then, that Arena’s success was built on the resident company format. Its resident actors over the years made up a list of luminaries: Robert Prosky, Frances Sternhagen, George Grizzard, Philip Bosco, Roy Scheider, Robert Foxworth and Dianne Wiest, in addition to Mr. Jones and Ms. Alexander. (Arena phased out its acting company in the 1990s, after Ms. Fichandler’s departure.)

“The company is the equivalent in the world of theater to the family in a social form; when you knock on the door, they have to let you in,” Ms. Fichandler said in an interview on the website of Theater Communications Group, an umbrella organization for nonprofit theaters.

“The people stick with you; you can make a mistake and go home again,” she added. “You can do something bad, not play a role well, and they let you get up on the horse again.’’

Today it is hard to imagine an American theatrical landscape as sparsely inhabited as the one Arena entered. Among the few notable ventures were the Cleveland Playhouse and the Goodman Theater in Chicago, which had established professional credentials in the first quarter of the century. The Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland had put on a seasonal program of Shakespeare beginning in 1935.

In the late 1940s, Margo Jones had established Theater ’47 in Dallas and Nina Vance founded the Alley Theater in Houston, and together, with Arena, they led a slow expansion through the 1950s of what became known as the resident (or regional) movement.

The Stratford Shakespearean Festival of Canada, now known simply as the Stratford Festival, which began performances in 1953, helped as well; its first artistic director, Tyrone Guthrie, founded the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis in 1963 at a time when the Ford Foundation was actively promoting professional theater around the country with significant donations.

Continue reading the main story

FROM OUR ADVERTISERS

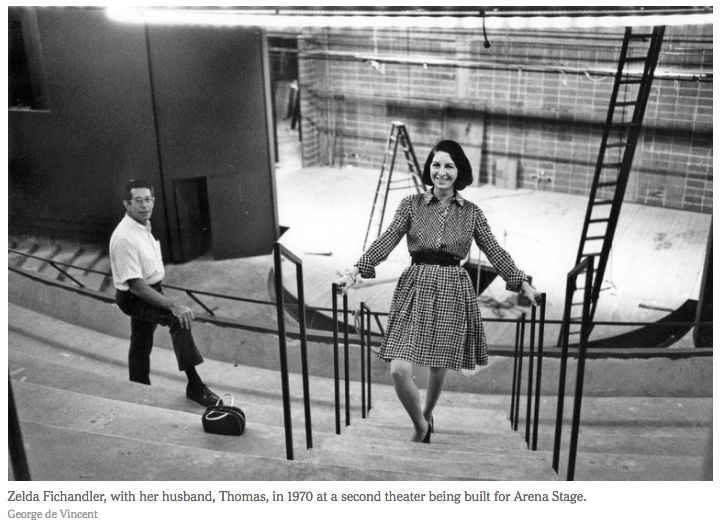

By then Arena was performing in a new theater in the round (more of a rectangle, really) of about 800 seats at its current location along the Washington Channel in southwest Washington. (The theater has since been renamed Fichandler Stage.) In 1971 it opened a second, smaller house with a thrust stage.

Today, Arena is a modern complex (renovated in 2010) of three theaters with a total of nearly 1,400 seats, putting on 10 or so productions annually with runs of a month or more and selling 300,000 tickets. With a budget of about $20 million, it is among the largest of the nation’s more than 1,700 professional nonprofit theaters and the foundation of theater in Washington. All the city’s 90 or so companies came into existence in the wake of Arena’s early success.

“Zelda Fichandler is the mother of us all in the American theater,” Molly Smith, the artistic director of Arena since 1998, said in a statement. “It was her thinking as a seminal artist and architect of the not-for-profit resident theater that imagined resident theaters creating brilliant theater in our own communities. A revolutionary idea. Her thinking and her writing have forged the way we were created and the resident nature of our movement.”

Ms. Fichandler was born Zelda Diamond in Boston on Sept. 18, 1924, and grew up mostly in Washington after her parents, Harry Diamond and the former Ida Epstein, moved the family when she was 4. Her father, an immigrant from Russia, became an engineer and inventor who worked for the National Bureau of Standards. During World War II he helped develop proximity fuzes, devices that detonated bombs as they approached their targets. His wife was a secretary in his laboratory.

Ms. Fichandler, who was interested in acting, graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School in Washington. At Cornell University, she read Chekhov in Russian and studied piano. She planned to be a psychoanalyst but left the sciences, she once recalled, after a near-disastrous lab accident involving hydrochloric acid.

She met her husband, an economist who had worked for the Treasury Department and the Social Security Administration and who shared her progressive politics, on a blind date in Washington. It was in a class at George Washington, she recalled in the Theater Communications Group interview, that the idea surfaced for a professional theater in Washington.

“I was in a class with Edward Mangum, who said, ‘Do you all know that professional theater in America consists of 10 blocks on Broadway and nothing much more? Touring shows, a lot of community theater, nonprofessional. How does this sound to you? How does this seem to you?’ And I said, ‘Wow. That seems awful.’”

They raised $15,000 to start Arena, whose first home was the 247-seat Hippodrome Theater, and on Aug. 16, 1950, the theater opened its first production, “She Stoops to Conquer,” the 18th-century comedy of manners by Oliver Goldsmith. Mr. Mangum directed it.

Ms. Fichandler’s first directorial effort was “The Firebrand,” a 1924 comedy by Edward Justus Mayer drawn from the autobiography of the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini.

Arena outgrew the Hippodrome within five years and eventually found a new home in a former brewery that came to be known as the Old Vat. Its first production there, directed by Alan Schneider, was the American premiere of the rewritten two-act version of Arthur Miller’s “A View from the Bridge” (the version familiar to today’s playgoers). A one-act version had opened on Broadway the previous fall.

Ms. Fichandler separated from her husband in the mid-1970s, though they remained friendly, continued their professional partnership and never divorced. He died in 1997. In addition to her son Mark, she is survived by a sister, Joyce Simons; a second son, Hal, and two grandchildren.

In 1984, Ms. Fichandler, citing her devotion to actors and actor training, became the chairwoman of the graduate acting program at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, a post she held until 2009. She helped train more than 500 students — among them Marcia Gay Harden, Billy Crudup, Rainn Wilson and Debra Messing — many of whom made their first professional appearances at Arena Stage.

“She had a dual devotion to the Arena Theater and to N.Y.U. Tisch, and to her, one part couldn’t exist without the other,” said Laurence Maslon, the associate chairman of the graduate acting program at Tisch and the author of a history of Arena that was published in 2000.

In the early 1990s, after stepping down at the Arena, she served as artistic director of the Acting Company, a performing and training troupe founded by John Houseman and Margot Harley in 1972. She was awarded a National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton in 1996.

Ms. Fichandler described the role of an artistic director as a go-between, shuttling intellectually and emotionally between the world at large and the world of the stage.

“There’s a Russian word, which is ‘missal’,” she said in the Theater Communications Group interview. “It means thought, or idea. ‘Za’ in front of it is an intensive prefix, so it means the really deep, important idea.

“In theater,” she added, “ ‘zamissal’ is that connecting tissue, or that central conflict, that, if you find it, will explode the meanings of the play, the reverberations of the play, and wake the audience up to a new perception of reality. That’s what we mean, I think, when we say that theater has the capacity to change lives, to change the world.”

Correction: July 29, 2016

An earlier version of this obituary misstated the year in which Ms. Fichandler stepped down as chairwoman of the graduate acting program at New York University. It was 2009, not 1997.